Racism in Former Model C Schools: Apartheid’s legacy lives on

Students at Cornwall Hill College in Pretoria taking a stand against racism. Photo by Deann Vivier/News24

Written by Naledi Sikhakhane

In a space of two weeks, there have been two incidents of racism in high schools that ended in standoffs between parents: white parents on one side, Black parents on another. Chests up, rapid breathing, curse words being hurled across the police forming a blue line between the Black and the white.

It is 2022. Twenty-eight years after the end of apartheid in South Africa.

One incident happened in a high school in Randburg where a grade eight student was beaten up by a white senior student and insulted for playing amapiano – a variety of urban house music – on his phone during a break.

Black learners and parents protested outside the Cornwall Hill College in May 2021, alleging institutionalised racism in Centurion Johannesburg.

Singo Ravele is a student who gave a powerful speech detailing how her fantasy of being accepted into the prestigious school turned into a nightmare as she was consistently discriminated against.

"My first and most vivid memory of racism happened when I was only in grade four, I was happily on my way to break when a teacher stopped me. She had this huge frown that encompassed her whole face and swallowed me whole. She looked me dead in the eyes and said 'Your hair is unpresentable, it's messy and it's not the Cornwall way,’” said Ravele.

The teacher told her she would look better with her hair chemically straightened. She never wore her hair naturally again, she began to resent it.

These “incidents” have been so frequent that we must stop calling them “incidents” because they are a culmination of daily microaggressions, stereotypes, prejudices and discrimination. Decades after apartheid, the systemic oppression of people of color is more prevalent than we as the “rainbow nation” care to admit.

To understand (and potentially stop) racism in schools, we need to look back:

Model C schools are previously only white schools that integrated after apartheid, they had their systems. Teaching in English or Afrikaans as the medium of instruction, these schools are some of the best in the country because they have spent up to centuries perfecting their infrastructure, teaching models and extracurricular support to provide students with a holistic learning experience. Black parents wanted this for their children too – so post-apartheid, the working and growing middle class took their children to these schools and their children got the kind of education that their parents couldn’t have.

Schools in Black areas have scant infrastructure, no playing grounds and overworked teachers. To quantify this, if there are only 16 classrooms for the only high school in a rural area and 2000 students are attending that school, then each class will have to house more than 100 students a class. A teacher needs to be able to give each child individual attention for an optimal learning experience and the best number for this is to have 20 to 35 students in a class.

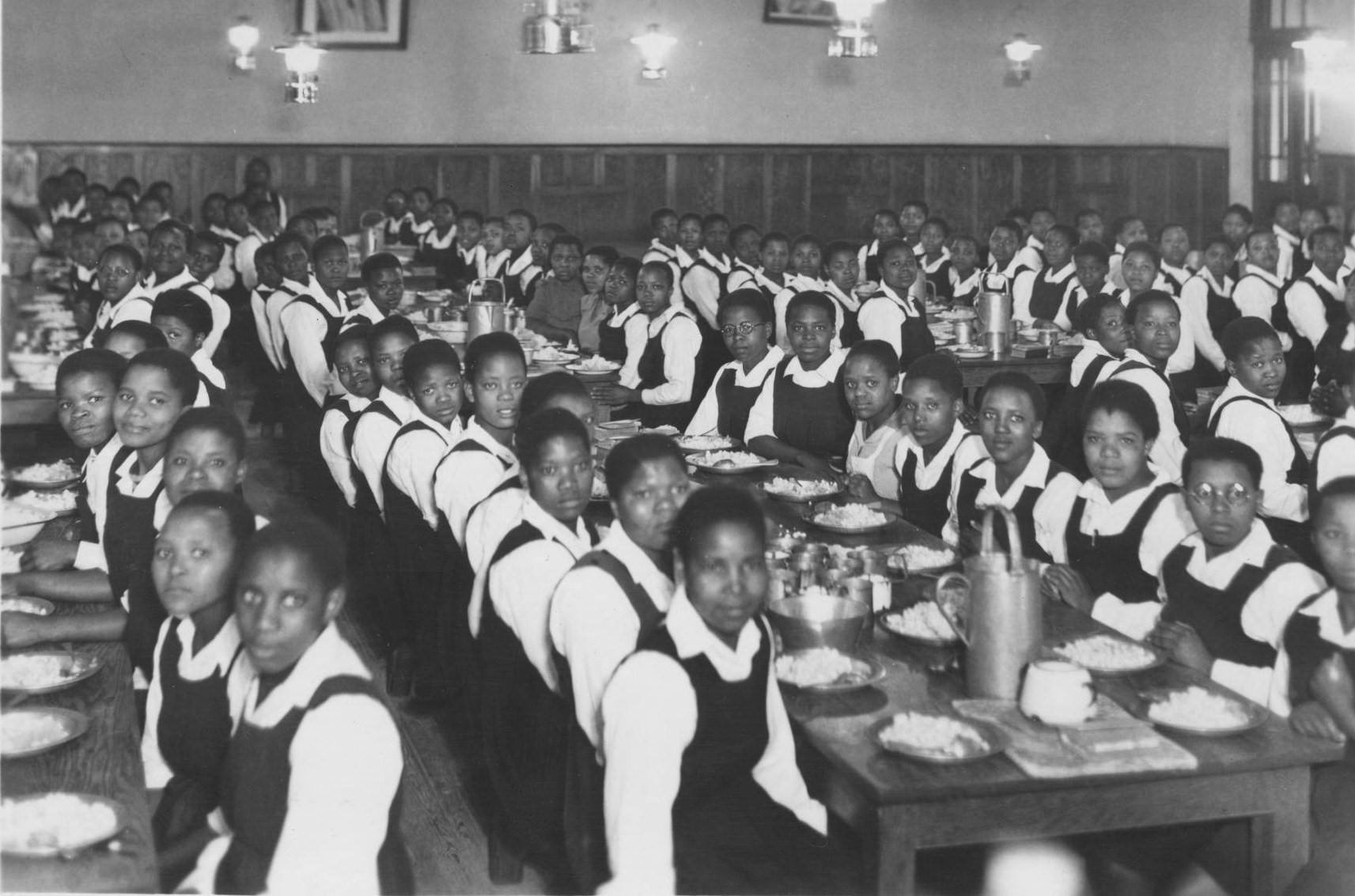

Pictures of student girls at mealtime in the girls hostel at Blythswood Institution around 1953. Read more here.

The condition of schools in predominantly Black areas is also the legacy of apartheid and the Bantu Education Act, which was implemented in 1954.

Bantu education was an inferior education system that essentially ensured that Black people could fulfill their duties well as unskilled workers and would know just enough English to take instructions. The system wasn’t intended to create doctors, lawyers or pilots, let alone jobs that are more relevant today – social media managers, careers in artificial intelligence, coding and so on.

So Black parents find themselves in a debacle: they have to choose how to give their kids a fighting chance to make it in the world. One path means their child can study in a class with 20 students; have extracurricular activities such as music or drama; play sports on state-of-the-art grounds with coaches that can call in scouts – or better yet – play on sports teams that are known for feeding national teams – all while facing racism.

The other path means they have to take their children to a local school in the township or rural area where there are limited classrooms, playgrounds with not so much as a patch of grass, goalposts or hoops. If there is any music and drama program it is because there is a passionate teacher who takes it upon themselves to start it, calls the students after school, pays out of pocket for transport to competitions and maybe choir uniforms – with no instruments and no funding.

The upside to the schools in previously disadvantaged areas is your child has a chance at being happy and confident because no one questions their presence in the space. No one remarks about their hair being untidy in its natural form. No one says “I like how you speak English, you’re very smart.” No one tells your child they can’t wait to see them "work in retail or as a car guard” or “I’m wasting my time with the Black girls, they'll be pregnant by 17.”

It is almost as if there is a racism handbook white teachers read from. Every time an incident happens, social media is outraged, news outlets follow the story, a member of the Executive Council in the Department of Education goes to the school, they promise to investigate or intervene to restructure racist policy, there might be a suspension or firing and the school will support this and say this was an ‘isolated occurrence.”

The country forgets, two months down the line teachers are accused of calling Black students animals, saying “this isn’t a shebeen” or “go to the township, we don’t speak that language here” when a student speaks one of their mother tongues even during breaks (there are 11 official languages in South Africa).

When students report these incidents they are reminded of how privileged they are to go to such a prestigious school or that they are over-sensitive and make everything about race.

Muslim students have to fight for concessions to wear hijabs, pants and are told to remove their beads as it “clashes with the uniform.” All schools have a dress code and code of conduct, it is necessary and crucial to maintaining a conducive learning environment. The qualm comes about when it excludes all things that are not white: “If you want to be here be more like us, relax that afro, speak English and Afrikaans, be Christian, and even then if we can’t get see beyond the color of your skin, don’t mind our little remarks about your whole race being somewhat inferior we don’t mean you, you're different.”

The issue is not just Black and white, there are a lot of grey areas. Yes, some mixed-race schools foster a healthy environment for cultural diversity and there are a lot of schools in predominantly Black areas that provide excellent results. But we can no longer ignore the students suffering daily purely because they are Black, mixed-raced or Indian.

There is a generation of babies born in the 2010s that can barely pronounce their own names correctly because their parents speak English with them all the time and they only speak English in schools. These parents are the ones who were shunned for speaking Tswana, Zulu, Xhosa, SeSotho and all the other official languages.

This has given rise to a generation of Black people who have identity issues, self-hate, low self-esteem, or who have a deep mistrust for white people as a race and are constantly in a defensive stance from years of trying to explain that there is nothing wrong with them, their language, their hair, culture, their people.

Naledi Sikhakhane (she/her) is a journalist and writer who aims to bring about social justice in her work. She covers migration, women, the working class and other groups that need platforms to be heard and seen. Her work is on New Frame & MeetingofMinds UK.