The Right to Read: How National Reading Month Applies to Youth in Prisons

Each year schools, libraries, literacy groups and community organizations celebrate National Reading Month by highlighting the importance of reading in classrooms across the United States.

But how should this month be recognized by the nearly 60,000 youth under age 18 currently incarcerated in the American juvenile justice system?

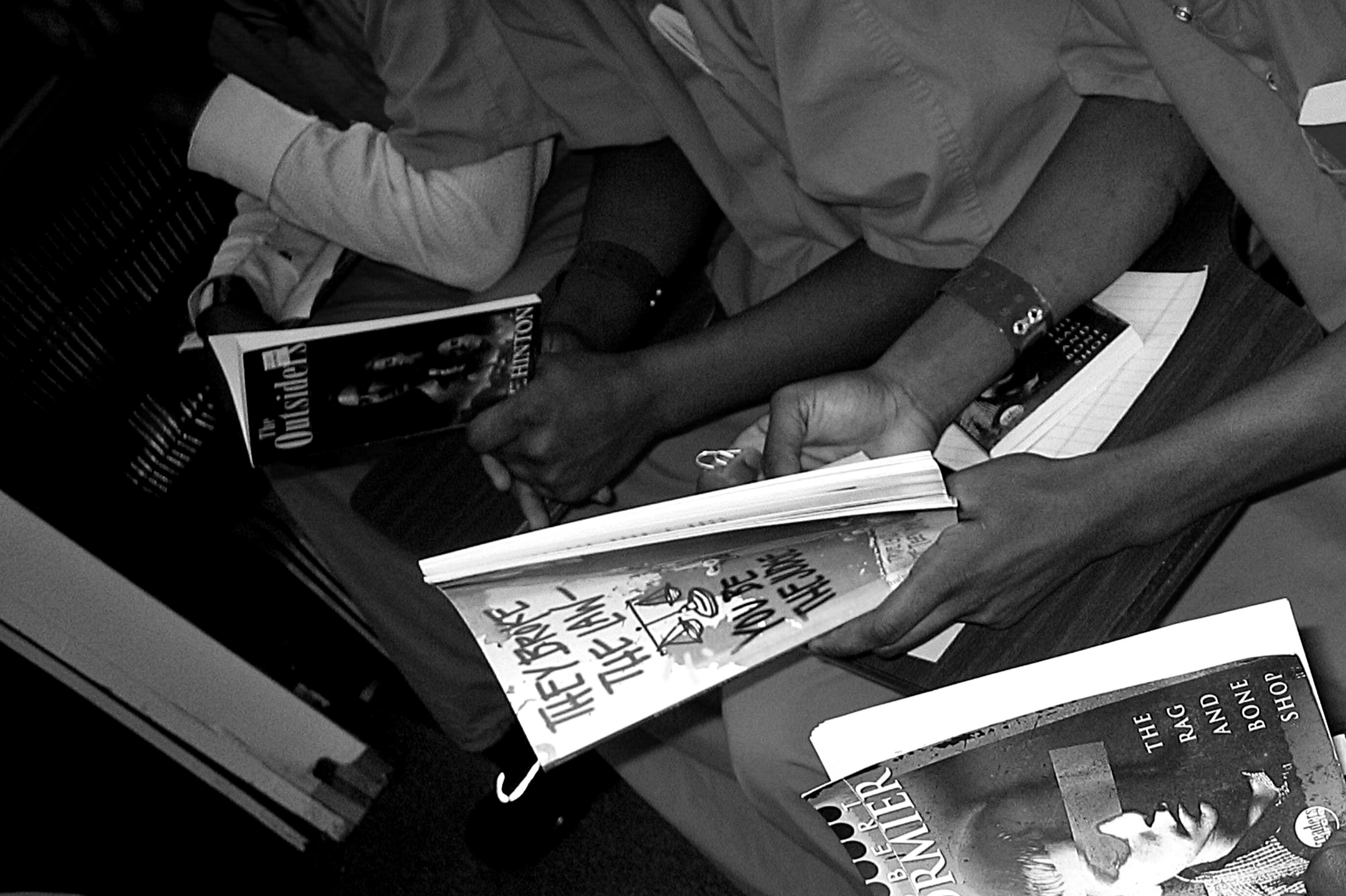

Photo source: Free Minds Book Club

Book censorship in American prisons has recently begun to come back to national attention. After interventions by legal organizations like the American Civil Liberties Union and the Education Justice Project, as well as a report published by PEN America, the public is beginning to understand just how hard America’s prison systems work to keep our most vulnerable from being able to read.

The report, titled “Literature Locked Up: How Prison Book Restriction Policies Constitute the Nation’s Largest Book Ban,” analyzed the policies and procedures at prisons across the U.S. and found that they typically lack consistent, formally written rules and therefore lack accountability from the bottom up. Books are often banned or withheld in the mailroom for arbitrary reasons.

EJP and Danville Correctional Center in Illinois faced conflict after books discussing Black history and other topics that promoted diversity and inclusion were removed, along with the educational programs they provided to those incarcerated.

"That sent a message to our students, who are predominantly African American men, about the continued power of the prison administration over their lives," said Rebecca Ginsburg, director of EJP in an NPR article.

These book bans have long been justified by prison officials who say reading is a privilege and that certain books could pose a security threat to their facilities. These statements have yet to be validated and are more likely to stifle the ability of people in prison to gain access to materials they could use to educate and empower themselves.

It has been found, however, that improved access to education while incarcerated directly decreases recidivism (the likelihood that a person will return to jail after being released) by up to 13 percent. In a study by the RAND Corporation that assessed the link between education programs and recidivism rates, it was also found that for every $1 invested into the education of someone in prison, communities save $5 in the number of taxpayer dollars used to incarcerate people.

“As a society, the U.S. must articulate and defend the right to read in prison. Otherwise, the nation’s largest book banning policy will remain unchallenged.” Literature Locked Up, PEN America

For our youth, this could mean a connection to the outside world and to ideas that motivate them to continue their education. And especially for the 35 percent of Black girls and 42 percent of Black boys who are over-represented in the juvenile justice system, access to diverse books written by Black authors compounds the already-existing effect of positive representation in the media.

In honor of National Reading Month, Better to Speak looks forward to shifting the focus of our annual book drive into a longer-term initiative to highlight the punitive practices within the criminal justice system, and discuss the overlaps with our previous work of promoting youth literacy and diverse Black literature.

Formerly known as Better to Speak: The Book Drive, The Right to Read initiative aims to bring awareness to inequities in access to literacy and education for Black youth in schools and prisons, and improve access to books for affected communities in Washington, D.C. and Metro-Atlanta, GA.

Check out these additional resources on book censorship in American prisons: